CWs: Mention of mental health struggles, grief, trauma, and suicide ideation.

“Shame is the opposite of art” is a quotation from this Ask Polly article by Heather Havrilesky, titled “I’m Broke and Mostly Friendless, and I’ve Wasted My Whole Life.’ This is like an advice column you’d find in a newspaper. A person going by “Haunted” describes her circumstances as a 35-year-old woman who has recently broken up with her partner, has spent most of her life traveling and having a trail of new jobs and failed relationships under her belt. She keeps moving and not planting roots. She also used to be creative and now feels jealousy and resentment toward other artists.

I used to consider myself creative — a good writer, poetic, passionate, curious. Now, after many years of demanding yet uninspiring jobs, multiple heartbreaks, move after move, financial woes, I’m quite frankly exhausted. I can barely remember to buy dish soap let alone contemplate humanity or be inspired by Anaïs Nin’s diaries. Honestly, I find artists offensive because I’m jealous and don’t understand how I landed this far away from myself.

She had a breast cancer scare, she’s in debt, and she’s looking to freeze her eggs because she feels as if her hourglass is running low, and she’s wasted her life.

I’m trying, Polly. I am. I’m dating. I’m working out and working hard. Listening to music I enjoy and loving my cat. Calling my mom. Yet I truly feel like a ghost. No one knows who I am or where I’ve been. I haven’t kept a friend, lover, or foe around long enough to give anyone a chance. What’s the point? I don’t care for my job. I’m not building toward anything, and I don’t have the time or money to really invest in what I care about anyway at this point. On top of that, society is telling me my value as a woman is fading fast, my wrinkles require Botox (reference said poor finances), all the while my manager is asking for me to finish “that report by Monday.” Why bother?

[…]

I used to think I was the one who had it all figured out. Adventurous life in the city! Traveling the world! Making memories! Now I feel incredibly hollow. And foolish. How can I make a future for myself that I can get excited about out of these wasted years? What reserves or identity can I draw from when I feel like I’ve accrued nothing up to this point with my life choices?

I’d highly recommend that you read this article before reading what I have to say. I often re-read it when I’m feeling low and aimless. I remember reading it at five in the morning before I went to my shitty supermarket bakery job, and it made me cry and feel better about myself.

Going with the ghost comment, Heather’s response characterizes Haunted’s perspective with the metaphor of a haunted house she’s trapped inside.

Shame creates imaginary worlds inside your head. This haunted house you’re creating is forged from your shame. No one else can see it, so you keep trying to describe it to them. You find ways to say, “You don’t want any part of this mess. I’m mediocre, aging rapidly, and poor. Do yourself a favor and leave me behind.” You want to be left behind, though. That way, no one bears witness to what you’ve become.

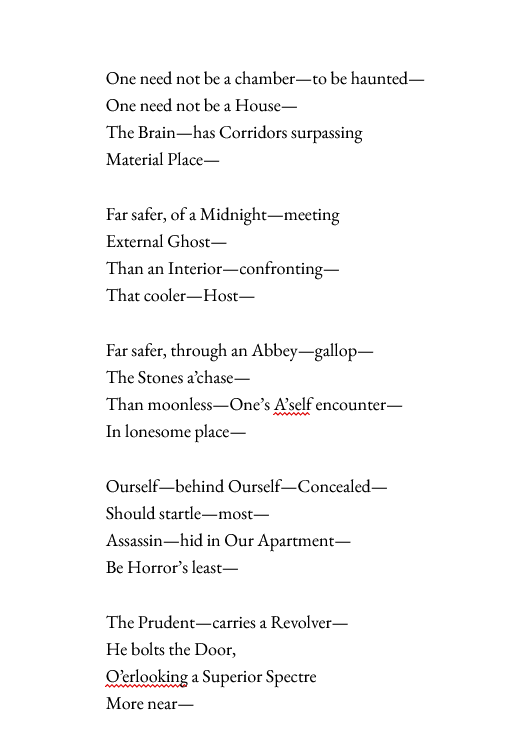

I know what this is like, and I see a lot of authors trapped in their own haunted houses—feelings of shame and inadequacy. Every misstep feels like a colossal, irreversible calamity and symbol of your failure that everyone can see. It reminds me of this Emily Dickinson poem:

My early twenties were some of the toughest in my life, full of grief, trauma, and loneliness. From the age nineteen to twenty-four, I dealt with crushing loneliness and daily suicide ideation, and my anxiety became so terrible that I would curl up in a ball on the floor, feeling like I was going to die. Even after I began to improve, for years, I was trapped inside this Hell I had to very painfully work to deconstruct, but it’s hard. I know it’s hard.

Don’t get me wrong. I have bad days. I sometimes have feelings of futility and hopelessness. I get frustrated and depressed. The difference is that I’m able to be reasoned with by either speaking with myself or my friends. It’s something that you have to work at every year, every day, to listen to your feelings and speak to yourself like you’re speaking to a sad friend—accepting the feelings but knowing when to challenge misconceptions and assumptions you’ve constructed out of shame. If you had a friend saying that they were a failure and nothing they do will ever be enough, you would comfort them while hopefully pointing out the ways shame has distorted their view of who they are.

The first and most difficult step is giving the problem a name, but it’s still frustrating when you know there’s a problem but not what the solution is. And any advice feels dismissive because no one can truly understand. An unfortunate thing about retrospect is that it only works when you’re inspecting and analyzing the past. Retrospection is also very good for art—as Havrilesky says, you take the splinters and examine them.

The haunted house I was in affected my writing. I wrote because it’s something automatic, something I can’t stop doing. Hell, people tell me to take a break, but I feel like I’m losing my mind if I don’t write, even when I’m having those periods after I finish a big project where I feel depressed and aimless and torn over what to work on next. Sure, I have hobbies. I like reading books, listening to music, taking photos, watching movies, and playing video games, but if I don’t have my writing and my characters, I don’t have one of my greatest comforts.

During the hard times I experienced even after grad school, I would write, and I would hear, “Morgan, I wish I could write as much as you.” But I was unhappy. Not because I was writing too much, but I would often complain that I felt like my work was passionless and meaningless. It wasn’t, but I was troubled inside.

Inside my head, I could hear my graduate workshop professor going, “This is so bad that it can’t be workshopped. How do you expect to get a literary agent when you write about things no one cares about?” The audience in my head was assumed to be hostile and inspecting my work for every flaw, looking at me like I was hopeless and amateur. I always worried about trying so hard and always being inadequate. What if I write a hundred books, and none of it matters? All these words, and they don’t connect with anyone or feel real.

I felt aimless and like a jack-of-all-trades, master of none. I hated myself for being good at writing and not engineering when my family insisted that I get an “actually useful” job in STEM. I’ve struggled to keep a stable job. A lot of the jobs I’ve had were exhausting and soul-draining, where I felt disrespected and disposable. Others don’t pay well. Often, I’ve looked at a lot of my old peers and go, “I should’ve done what they did.”

I see a lot of authors trapped in haunted houses, and it can be hard to know what to say. Authors, worried about not writing enough and not having a big enough backlist. Worried about being failures, desperate for external validation—but even when they look at what they’ve accomplished, things that so many unpublished writers have dreamed of, they feel unfulfilled and, at the end of the day, say that they’re failures. The external validation—1,000, hell, 10,000+ books sold, trad pub offers, lit agent offers, conferences, interviews, fanart, fanfiction, glowing reviews, awards—is never enough. “No, the things I was able to accomplish don’t matter in the end.” They look at the bad. A book that didn’t sell as well as the previous one. A book that was badly received, and this is proof that they’re a failed author.

There’s a lot I want to say, speaking as an indie author. It’s almost overwhelming, and of course, I’m aware that everyone is different. Being an author is frustrating. When you’re starting out, you’re still experimenting; you might not know what outlining process works for you, or if you need to write without an outline. You try everything from discovery writing to the snowflake method, and it feels like pulling teeth. Or maybe you’re like me, where I do have some consistencies—viewing characters as having masks/walls that must be broken down or like roses that go from buds to blossoms—but I tend to have processes that fit the story. My strategy changes. I’ll spend far more time outlining and worldbuilding for a longer fantasy work than, say, a novella. For shorter works, my considerations are different.

But if you’re just starting out and already wondering if it’s over—no, it’s not. Even if you have a few books out, and you’re still struggling—no, it’s not over. You can always make a new cover, write a more engaging blurb, reach out to other authors and organize an event.

Also, a book isn’t “dead” if it hasn’t found its audience right out of the gate; it’s a marathon, not a sprint. There’s always different events you can do with other authors where new readers discover your work. You can even make one up yourself.

Maybe you wrote a book that was poorly received and got a bad score on Goodreads—so what? Seriously. So what? Hell, let’s say it’s true—you wrote a bad book. Let’s say the worst possible scenario is true, and the criticisms are right.

And? I’m not trying to be dismissive, but a bad day doesn’t make a bad life. One bad book doesn’t make a ruined author career—insert highly successful and prolific authors that have books that people dislike here. Look on the bright side, you’re an author, not a heart surgeon. (Unless, of course, you are also a heart surgeon, in which case, good luck!) A heart surgeon has a bad surgery and makes a mistake, and well. No one is going to die because you wrote a disappointing book. Writing and art are about making mistakes and learning from them. With all the books out there, most people will probably forget and move on.

Readers will give you a second chance; I have authors like Maggie Stiefvater and Leigh Bardugo where their debuts didn’t resonate with me, but I liked later books, and I tend to expect improvement as time goes on. I like to secretly hope for a redemption arc for most authors I read when I don’t initially love their work. And if an author who has had good books then has a flop, well, no one is going to put out 10/10 work all the time. You stumble? The book doesn’t sell? The book isn’t good? Write another book. And then another one.

I’m not saying it’s easy. It’s not. But we only get one shot at life and telling our stories.

No book is perfect. Writing a bad book isn’t so dire—and especially if you’re young and only just beginning, you have your entire life to make a career. If you end up writing twenty books, and that first or second one was badly received, who cares? An author writes a bad book—well, I’m not sure I quite believe in Sturgeon’s Law where 90% of everything is crap and only 10% is good, but plenty of books range from bad to okay/mediocre, and life goes on. You have to learn and then go on, too. As Erin Bow says: “No writing is wasted: the words you can’t put in your book can wash the floor, live in the soil, lurk around in the air. They will make the next words better.”

I’ve seen so many indie authors worried about a book they’ve already published. They watch the Goodreads reviews like a hawk, and they agonize over every mentioned typo or plot hole, and then they revise the book five, six times. Maybe more. I once knew an author in real life who did this, and I begged them to stop looking at reviews; I never look at reviews unless I’m tagged on social media. After I make a book and save the Goodreads link to share on my website and give to ARC readers, I don’t look at the book page. Ever.

Anyway, this author grew testy and said, “Well, unlike you, I have anxiety, so I need to see every review to ease my anxiety.” (I have Generalized Anxiety Disorder—see curling up on the floor and imagining every catastrophe to the point of thinking I would die.) They then proceeded to talk about how much of a failure they felt like at every low review, and they kept revising and re-uploading the book to try to make it as perfect as possible. I swear they did this seven times.

The time for revision is before the book is published. You have to move on. I’m serious. Deathly serious. You’ll drive yourself mad and spin your wheels like a car stuck in mud if you focus on one book and every little imperfection—every single book is flawed. Every single one. A typo on page 257, a scene that could be better paced. The best books I’ve ever read have flaws and people who insist they’re the worst things they’ve ever read. You can’t spend your entire life fixated on what people think about one book while not progressing with others.

I know it’s a cliché, but you’re only a failed author if you quit. And hell, plenty of authors give up and then lead decent lives. Me? I can’t stop writing. But you’re not a failed author if you write a bad book or get a bad review—all books have people who will read them and not connect with them. The pacing is too fast or too slow. The prose is too simple or too flowery. Too much romance. Not enough romance. Too slowburn. Too fastburn. If you even had just one person resonate with it and love it, then I don’t see that as a failure.

It’s like a dartboard. You want to aim for everyone in the bull’s-eye loving the book. You write for those people who you know will Get It. And then, as you move away from the bull’s-eye, you have people who still enjoy the book, but maybe they’re not 100% the targeted audience. And then, there are people who absolutely aren’t your target audience, and you shouldn’t worry about appeasing everyone. Someone who wants a Lord of the Rings-esque fantasy probably won’t like a romantasy, and that’s okay.

You have to know what criticism to accept and learn from and what to let roll off your back; you can’t make your book into something every single person loves by editing it one-hundred times. In fact, at that point, after so much whittling down, you’re making a book that will appeal to no one because of how much it tries to reach the middle of an impossible standard. All it makes me think of is this line from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment: “Your worst sin is that you’ve destroyed and betrayed yourself for nothing.”

It can be hard to give advice, even when I see these perspectives, and I know what it’s like because I’ve been there. I’ve been through the morass of transitional parts of my life where I felt like I was just rotting away while everyone else was doing something great and worthwhile. I’ve regretted and told myself I should’ve been literally anything but an English major who wrote twenty-five pages about the queer aspects of the Faust myth—even though I can’t think of anything I would rather do if I had the opportunity to reverse time.

I’ve been in my early twenties and worried that my writing would amount to nothing; I went through a period of not writing and finishing anything at all, and even when I did complete a book, I let it sit in my Google Drive because I worried about the reception.

It wasn’t until I got a stomach ulcer that completely wiped me out and had me in bed eating peanut butter crackers and cantaloupe slices that I thought about what I wanted out of life once I felt better. What would I do that I should’ve done when I was healthier? Because life is both very short and very long, and there’s no point in writing something you don’t have your entire heart in, and there’s no point in holding back, in regretting what you were too afraid or ashamed to share. Sure, undeniably, there’s a bit of egotism, a sense of “Yes, not only do I love the books I write, but I think they’re worthy of being read and bought.”

No one can write a perfect book, but I love every single book I’ve put out; I love them so much that I dream about the characters, and I don’t regret a single one. I love the eroticism and tenderness in A Flame in the Night; I love the nightly, foggy dreariness of Witch Soul as Millie looks up to see a moth trapped in glass. I love the misty seaside and dark woods in Providence Girls, and the cheap motels and abandoned Dollywood of King of Hell. And so on.

As I’ve mentioned before, I remember feeling joy when I wrote A Flame in the Night. I remember sneaking in words when I was supposed to be doing other things. The characters kept me entertained as I was scrubbing pound cake ring pans and my ankles felt like they were breaking. I didn’t worry about the word count or if my old graduate professors would be mortified that their promising student was writing vampire smut. I intentionally made the novella focused on the erotic aspect, and I had Léon make reckless and terrible choices—things I would’ve been afraid to write because I would have anticipated that reader in my head who would go, “This is unrealistic! No reasonable person would do this! Why would you go into the wine cellar with a vampire alone unless you’re short-sighted and horny?”

Realizing that I was miserable, realizing that I couldn’t go on in this trap I was stuck in, I wrote uninhibited—and something changed. It wasn’t even so much about the work being indulgent, even if it was; it was putting aside my shame. Know no shame and all that.

I think it makes sense for creatives to get down about their art; it’s a very sensitive and vulnerable undertaking. Eventually, you have to wake up and get out of these mental traps, but you shouldn’t hate yourself for feeling this way and try to suppress it. Sometimes, you have to sit with these feelings to eventually understand then.

Again, imagine you’re speaking to a sad and defeated friend. You have to be your best friend and number one fan—because if you aren’t the very first supporter when you’re all alone writing in whatever program you use, who will be? Even if I always have goals I haven’t met yet, art is never a waste—the joy of writing, the kind readers, the incredible friends and amazing artists and writers I’ve met, it’s all worth it.

Shame is the opposite of art. When you live inside of your shame, everything you see is inadequate and embarrassing. […] Shame turns every emotion into the manifestation of some personality flaw, every casual choice into a giant mistake, every small blunder into a moral failure. Shame means that you’re damned and you’ve accomplished nothing and it’s all downhill from here.

[…]

You need to discard some of this shame you’re carrying around all the time. But even if you can’t cast off your shame that quickly, through the lens of art, shame becomes valuable. When you’re curious about your shame instead of afraid of it, you can see the true texture of the day and the richness of the moment, with all of its flaws. You can run your hands along your own self-defeating edges until you get a splinter, and you can pull the splinter out and stare at it and consider it. When you face your shame with an open heart, you’re on a path to art, on a path to finding joy and misery and fear and hope in the folds of your day. Even as your job is slow and dull and pointless, even as your afternoons alone feel treacherous and daunting, you can train your eyes on the low-hanging clouds until a tiny bit of sunlight filters through. You are alive and you will probably be alive for many decades to come.

Hello! I’m Morgan, and I write romance, horror, and fantasy. I enjoy Gothic lit and vampires. My newest book as of typing, The Saint of Heartbreak, a queer romance in Hell about Judas and the Devil, is out now. More about my books can be found at morgandante.com.

Thank you for this. It is so beautifully put and I very much needed it today